Anna Mae Weems, a member of the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA), one of the unions that would later merge to become the UFCW, shared her memories of working with Dr.Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) on the 1968 Sanitation Workers’ Strike in the following article that appeared in The Courier.

The UPWA had long been a strong supporter of the SCLC. In addition to continually organizing conferences and legislative actions in support of equal rights for women and minorities, the UPWA donated 80 percent of the cost of SCLC’s first year budget and held regular drives to raise money for sit ins and freedom rides. When Memphis sanitation workers called on labor allies for help, Weems and other UPWA members heard the call.

WATERLOO – It was early 1968. A charismatic minister Anna Mae Weems had hosted on a visit to Waterloo nine years earlier and his organization needed help. She answered the call.

Weems, who had been active with the United Packinghouse Workers of America at The Rath Packing Co., and other labor leaders were called to Memphis, Tenn.

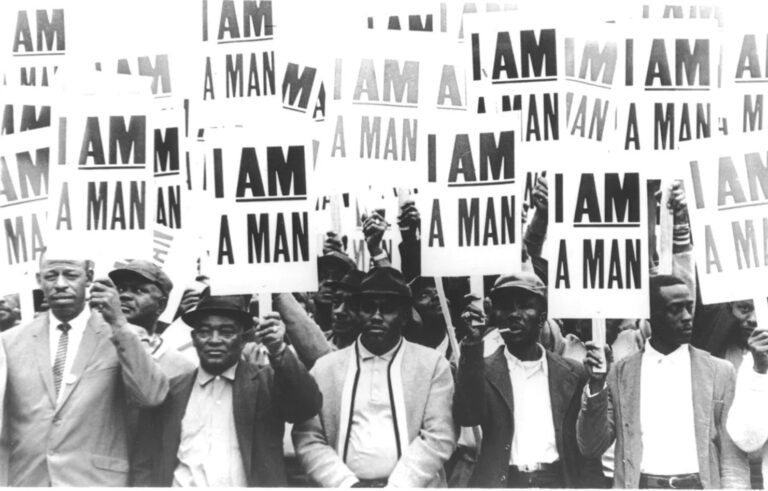

Unionized municipal sanitation workers, predominantly African-Americans, were on strike for better pay and working conditions. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference was called in to help. Other labor organizations also were called in.

That’s what brought Anna Mae Weems to Memphis for what would be her last meeting with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., SCLC leader.

“We marched down Beale Street and around City Hall,” Weems recalled. Through it all, King maintained a humble persona. “He was a common person. It wasn’t like I was sitting with a celebrity. He was like someone you knew all your life. He was for the good of the community all the time.”

Weeks later, on April 4, 1968, King was killed by an assassin’s bullet on a Memphis hotel balcony. Weems, home in Waterloo, reacted as many, with shock and horror.

The 50th anniversary of King’s assassination makes this Martin Luther King Day particularly poignant for many, including Weems. She escorted King around Waterloo in November 1959 as the young minister was starting to make a name for himself with civil rights activities in Montgomery, Ala. He met community leaders, spoke at West High School and at Iowa State Teachers College, now the University of Northern Iowa.

Fifty years removed from the tragedy of his passing, Weems said King’s death reminds us leadership is not for the squeamish but is still needed today on issues of justice and equality.

“He would want us to build on leadership,” Weems, 91, said. “ If you get good leadership in a community and you get that motivation and you get that influence, then you would have a community that’s unified. … You see, leadership is not for cowards. You have to know how to bring out the best in people.”

She supported King on some marches activities in the South.

“Some people would throw things, and he would say ‘Louder, children. Louder. They’re not hearing us.’ He would say things that are uplifting, not downtrodding.”

Weems said she and others were called to a meeting at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, now the home of the National Civil Rights Museum. It was where King frequently held meetings and was ultimately assassinated. A fellow Rath-UPWA member from Waterloo, Russell Lasley, became national treasurer of the UWPA, which supported the SCLC.

“We were called down there to help the garbage workers,” Weems said. “I was volunteering all around,” working under King’s friend and SCLC associate, the Rev. Ralph David Abernathy.

King sought conciliation, not confrontation, through organizational efforts, Weems said.

“Dr. King always had that saying that you should inspire, not intimidate. People would say things are real bad. Dr. King would say, ‘There’s no such thing as an unmotivated person.’ A leader should go in, work with a person and stir up the energy God gave him. … Bosses drive men. Leaders motivate.”

Weems first met King in Washington, D.C., in the late 1950s. He gave the invocation at a breakfast hosted by then-Vice President Richard Nixon. She invited King to Waterloo.

While some locally initially were standoffish to the young minister, Weems said others, such as the Rt. Rev. Monsignor E.J. O’Hagan, pastor of Sacred Heart Catholic Church, welcomed him with open arms. Burton Field of Palace Clothiers fitted the young minister with a heavier suit of clothes for the chilly November Iowa climate. He stayed at the Russell-Lamson Hotel.

After his talk at West High, Weems recalled, King stood behind the auditorium curtain, buoyantly asking, “Did I do all right?”

“He was intoxicated with love for his fellow man,” Weems said.

She learned of King’s assassination when called by a Courier reporter. “It was such a shock,” she said. She hushed her children and called the UPWA union hall to verify it. The secretary was in tears.

She later told The Courier, “Dr. King taught us that violence is not the answer; it only creates fear. The wound of racial injustice can only be healed by the peaceful balm of religion and morality. We must — and we shall — try to fill the void and move forward with brotherly love.”